This article was written with new inspiration from many conversations around the the Platform Cooperatives conference in NYC in Nov 2017. (What an inspiring conference!). Trying to wrap my head around sociocracy and its application to platform cooperatives, this is the second article I am writing about it (the first one is here but it is outdated).

Platform co-ops are a hot topic and a new hope. Could we re-build an alternative for the platforms we are using in a way that involves shared ownership and shared governance? Platform cooperatives are being formed as cooperatives, and some of them are designed as cooperatives of cooperatives. It is exciting to imagine how so much more people power could be unleashed if we managed to truly own and influence our immediate and our digital life in a way that is aligned with our values instead of giving up power and profit to a fairly intransparent, centralistic force.

Why I am interested in platform governance

To me, this is a core puzzle to solve in these times. Platform cooperatives will shape our lives in the future. Platforms are our opportunity to connect and meet our basic needs (which includes our digital needs) in a way that can either extractive (platforms run by non-coooperative corporations) or it can keep ownership with the people who maintain control over their infrastructure, their money, their data, their connections.

While shared ownership seems more doable, I see cooperatives struggle with governance. The desire is for cooperatives to be democratic (whatever that means), in alignment with the cooperative principles. However, the more members a cooperative has, the more separation there will be between the member voice and the staff/stewards who run the platform. (I will refer to the people running the platform as staff/stewards; for governance questions, it does not matter whether the role is a paid role; it can even be mixed staff with volunteers in a team.)

Why is it hard to be democratic in a large cooperative? Let’s look at an example. I myself am a member of a food co-op and of a credit union. While it is great to have trust that their operations are non-extractive and inclusive (and I do have that trust), my contribution to their governance consists of checking off a name that I don’t know on the ballot I am being sent once a year. Is that enough? Being a governance nerd and promoter of sociocracy — a system of egalitarian governance by those who associate together, best explained in this 4min video — I am often not impressed with the level of democratic participation in large cooperatives. And if you have ever been part of a election where the board lined up 5 people for 5 positions and expects the membership to rubber stamp the decision made in a board room, you might share my skepticism. Even more because majority vote of people we hardly know tends to prefer the people with a good name or a prestigious bio, not the people who deeply care.

More important that being able to vote I find that the members’ voice can be heard and can actually affect decisions made by those who run the operations more often than just every year for the elections. I prefer a system that is more fine-grained and more inclusive than just that.

Here are the patterns

Let us understand the problem a bit better.

- One piece of the pattern is the desire for democratic control for an organization that requires much less people to run the operations than there are members. This is not only cooperatives: town government requires a few hundred people to run it but wants to include the voices of a few ten thousands of people. My food coop has a few thousand members but is run by a few dozens. A platform coop can be run by 25 people and serve hundred thousands of contributors or “prosumers” (consumer/producers. Being inclusive in big numbers requires a plan.

- The operations have to run smoothly. A co-op cannot survive if is not financially sound and well-run. Like any business, running a platform requires expertise, team work and a long attention span. A platform cooperative needs to offer relevant, high-quality service that is just as convenient as the non-cooperative platforms’ service or it will not be able to replace extractive platforms. We cannot run a business solely on ideology.

- Being a cooperative, we want to hear member voices and have members participate in decision-making.

The ace up our sleeves

At first sight, it is much easier — in the short run — to run a business top down. In the long run, however, effectiveness and equivalence (“everyone’s voice matters”) are not mutually exclusive. Over time, a decentralized, inclusive and more considerate system will outsmart authoritarian micromanagement. Yes, we can have both inclusive and successfully run organizations. However, this comes at one condition: any approach that wants to be efficient and inclusive has to excel on clarity and intentionality when it comes to process. Intentional process is the ace up our sleeves! Processes keep our attention free to focus on what matters, ensure quality of our product, offer transparent solutions for decision-making, conflict resolution and sharing of power and tasks.

The assumptions I make

If you read my articles, you know that I assume that sociocratic governance is the best we have available. It is open, free, modular, versatile, inclusive, and tried and tested. Interestingly, for this article, I am using very basic design principles from sociocratic practice but not core sociocracy. Which means: sociocratic governance is not required to do what I am proposing here. But everything I write is bathed in the striving for combining effectiveness and inclusiveness through clarity and intentionality, which, for me, is what makes sociocracy what it is.

The basic assumptions I am making for platform governance.

- We have to separate the operational sphere from the membership/community sphere. They have very different experiences, perspectives and needs. You do not want “the community” run your operations. Running operations requires focus. We do not want to include 2000 members of a food coop on whether the coop should buy a new fridge. The fact that there will always be a core group of people doing the day-to-day work is an assumption I am making. (And my judgement is that if we do not accept this as a reality, it will just come back through the back door with informal “inner circles”, aka backroom decisions.)

- Separating feedback from decision-making increases inclusiveness. This is a principle from sociocracy that can easily be applied in any context: we can ask a huge number of people for feedback but making a high quality decision requires deliberation. Deliberation requires trust, relationship and a group size where people can hear each other: ergo decisions in sociocracy are made by groups of 4–7 people. Feedback in sociocracy is harvested from any reasonable number of people in the context. It sounds contradictory but it really works: we can listen to more people if we reduce the number of people in a team and are more intentional around listening to feedback. This also builds trust on two levels: (1) the trust that builds over time between team members. This trust depends on personal relationships and does not scale. (As much as I wish it did.) (2) The second-tier trust is the trust we build as and in an organization that listens well and acts with integrity and consideration. This kind of trust scales and is earned over time of consistent loops of listening, deciding and transparency. (Remember, processes are your best friend to be consistent and reliable.)

Given those two assumptions, we only need to interweave the operational sphere with the community in ways and places where this makes sense. This is what this article is about. The operational sphere and the general membership can be connected on different levels, through feedback and decision-making.

Design principles for platform coop governance

I propose that there are three different ways to connect the operational sphere and the general membership.

Let’s look at our starting point.

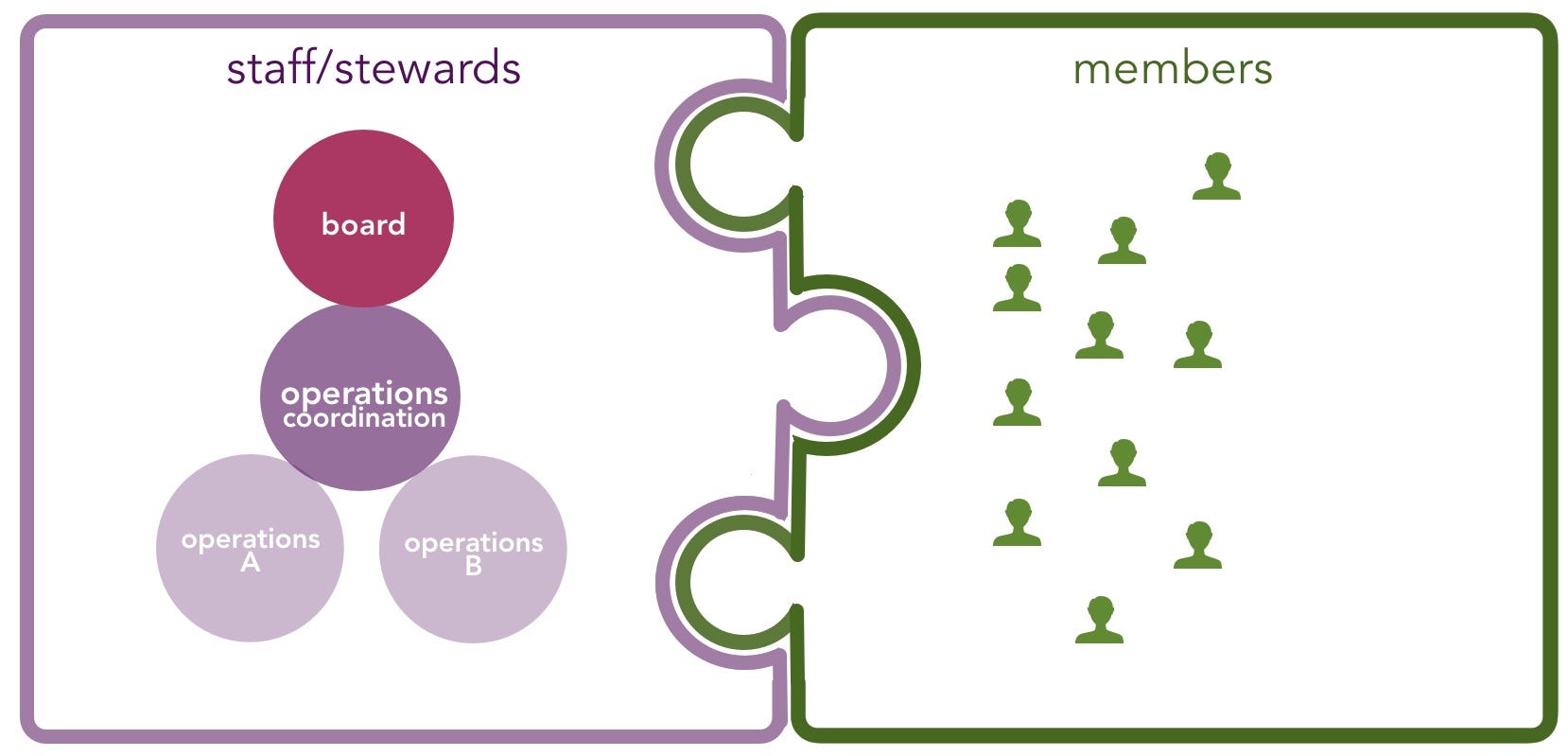

The divide: running the platform vs. the membership

This shows the staff/stewards and the members/contributors of the platform cooperative. In a non-cooperative set-up, this would be the end of the article. Customers would be separate from the business running the platform, both in terms of ownership and a on a governance level.

Note that in figure 1, I am assuming a sociocratic structure for the “business” part of the platform. This means two things:

- The board level is separate from the day-to-day operational level. The circle labeled “operations coordination” coordinates the work done and self-managed in the work circles. (In sociocratic contexts, this is called the General Circle.) The ED/CEO is the leader of that circle.

- The operations are being run and guided by the work circles, i.e. “operations A” team has full authority over what they are doing; another way of saying it is that the power is distributed.

(You can still run your organization non-sociocratically. This means you would give your members a say but you’d put your workers into a top-down context who then have to be unionized. A sociocratic organization does not require unionization because the workers are the managers and co-owners.)

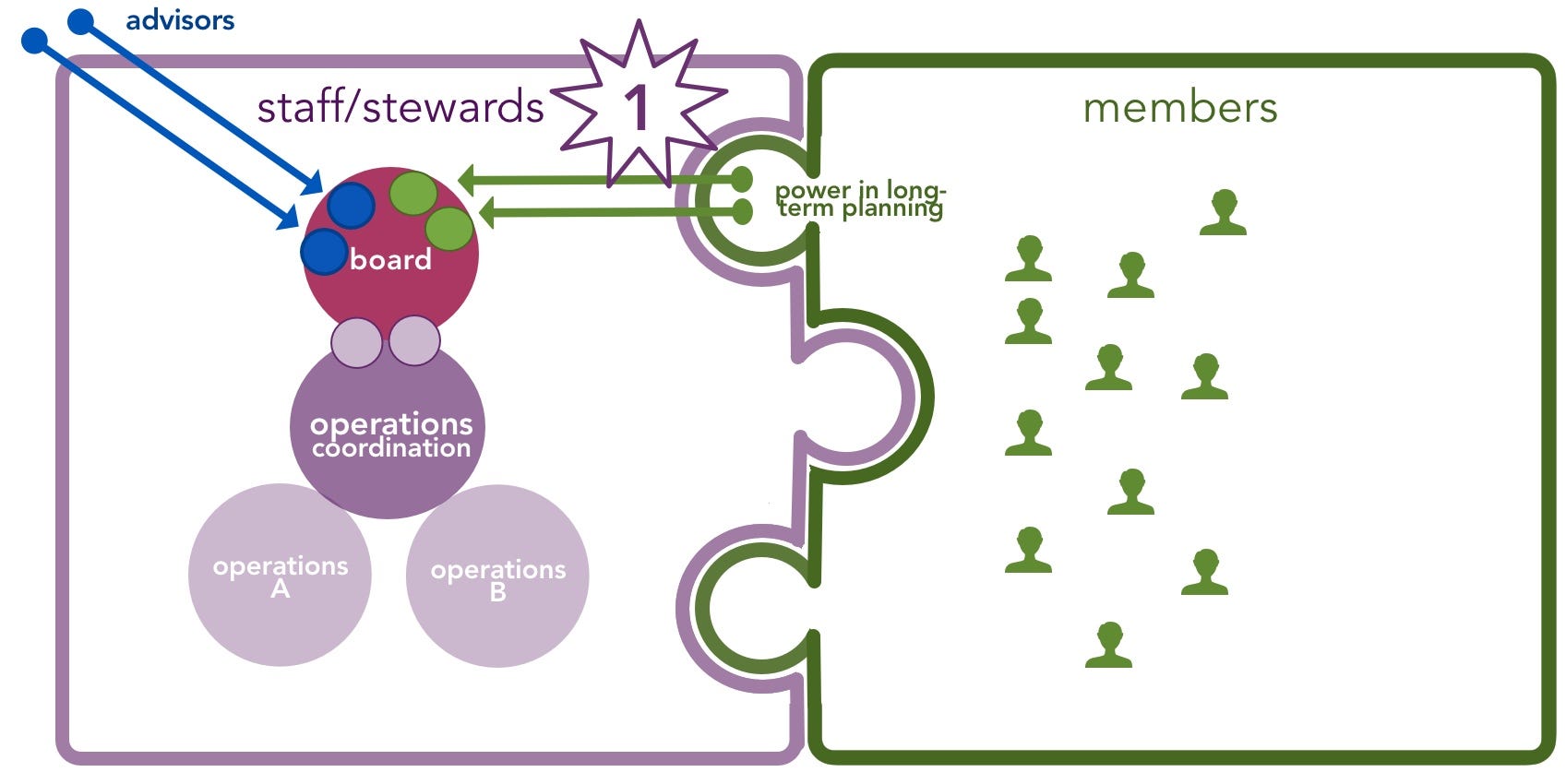

First way to connect: representation on the board

The first way to connect the community and the business is to give the membership representation on the board. Two people from the general membership join the board of the platform cooperative; they can be elected by majority vote but more preferred would be voting by preferential vote or even consent if that is doable given the group size. Most boards will already have outside advisors which is a good idea.

Two improvements from standard sociocracy that could be added here are:

- Giving the staff a voice as well as is done through sending two people from the “operations coordination” team to the board. (In sociocracy, this is called double-linking.)

- Changing the decision-making method from consensus or majority vote to consent. In majority vote can give away power: advisors and members can outnumber the staff, or advisors and staff can outnumber members. We want to create a mindset where everyone aims for a true win-win and therefore use consent decision-making: a decision is made only when no one has an objection. That way, we can be sure that no voice on board level can be ignored. (This is different from unanimous decisions where everyone has to agree; finding unanimosity is harder to find than a proposal that no one objects to.)

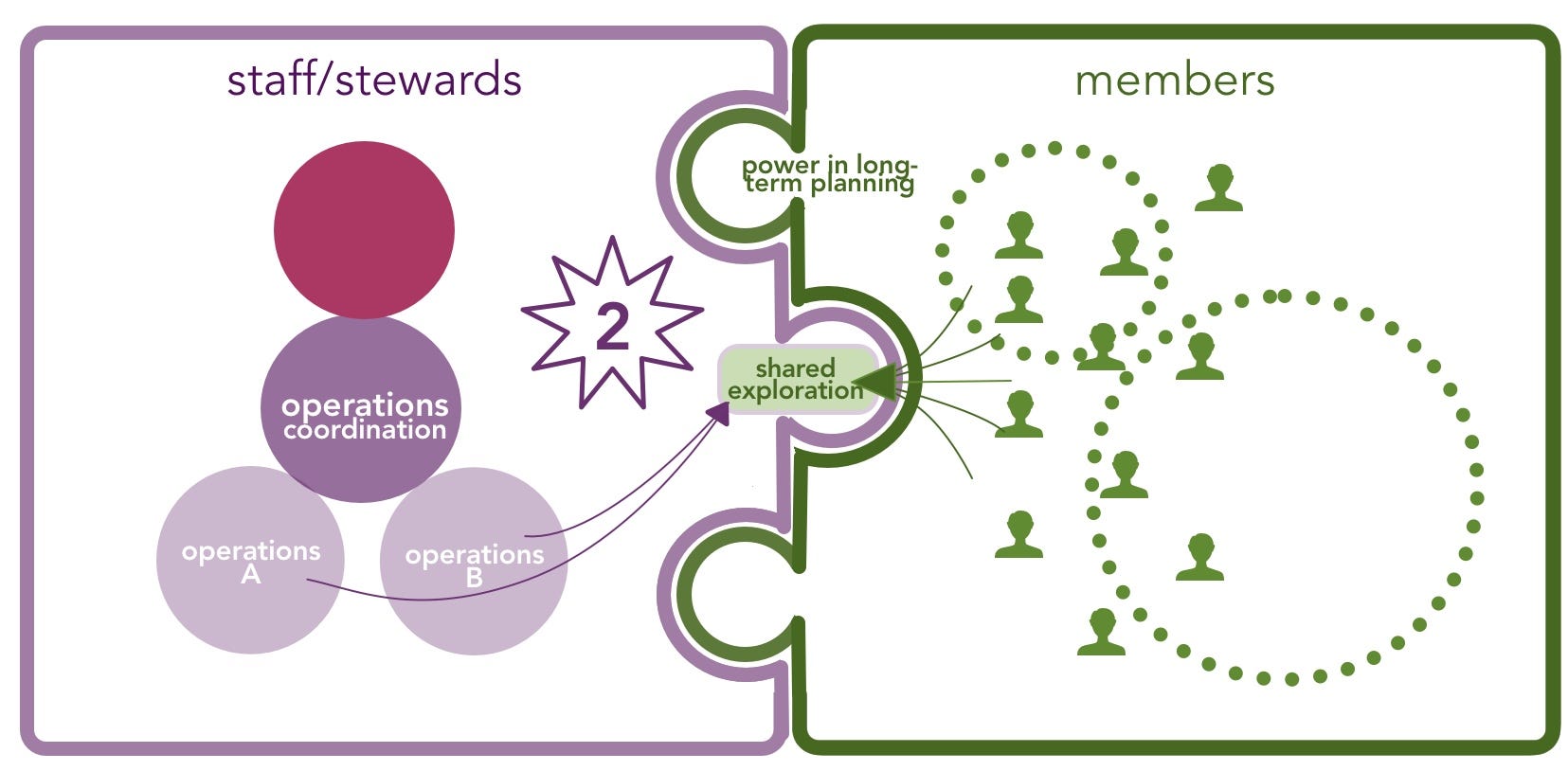

Second way to connect: open feedback lines for exploration

The second way to connect the two spheres is to create a place where members can explore and be creative. It is also the place where members can meet and create initiatives that benefit them, just as mutual support and training.

The easiest way to do this is to create and operate a forum, meet-ups, or something comparable.

The topics addressed in this shared exploration space can be highly relevant to staff/stewards. What features are users longing for? What struggles does our platform give members? Where can they see easy fixes? Where does the business have blind spots? How can we make this better?

From the staff perspective, we want to harvest this information because it is the most valuable information we can access. This can easily take up a lot of time so a co-op with paid staff members needs to find way of using this tool effectively and efficiently so that harvesting this information is empowering and not draining.

(A clean strategy from a sociocratic context would be to create a role in operational team that participates in the forum explorations related to its work; one or two people from each operational work can “listen in” and weigh in. The reason I would create a role and elect someone into the role is also because some enjoy this exchange more than others, and some people communicate better with community members than others. It is best to be intentional about this choice.)

Staff or stewards will get inspired and informed by this shared exploration. As I come from a sociocratic context, I take it for granted that meeting minutes and financial information are shared transparently throughout the organization which will inform the members so they can be relevant input-givers.

From the member side, this is where workers/stewards will explain why certain decisions are made, what the context was, what pros and cons were considered and went into the decisions. This is where information is shared in a transparent way and trust is earned. This is where the small grains of sand in the machine are dealt with before they turn into rocks. This is also where members can meet each other, can form alliances and self-organize.

This is also the place where non-members can weigh in or read up on what is being discussed, for instance prospective members, non-member clients. Sometimes organizations have blind spots that leave out stakeholder groups, voices from the larger community, or individuals that are not eligible for membership in the co-operative on economic grounds or due to time constraints.

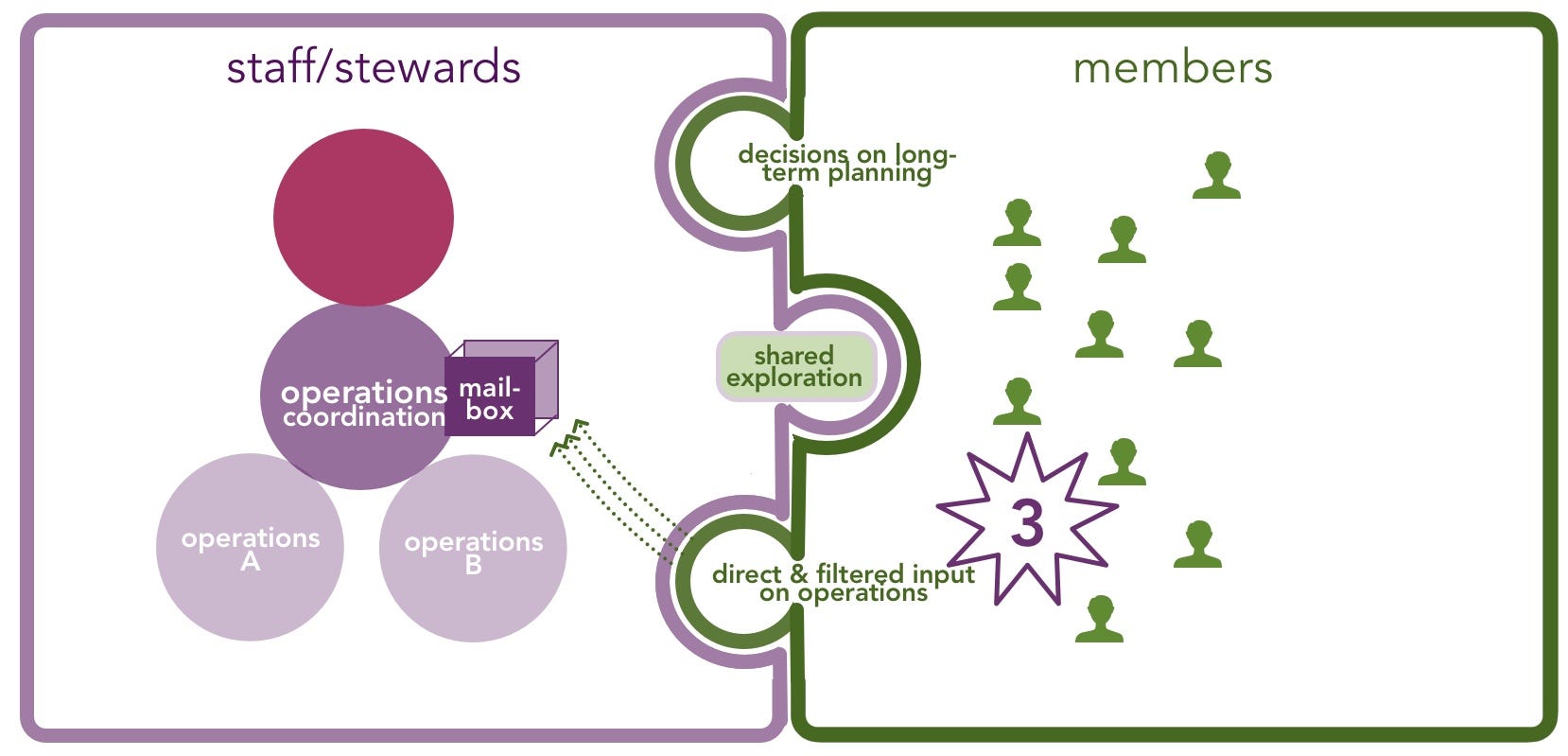

Third way to connect: the mailbox

In a perfect world, the first two way ways to connect the two spheres might be enough. However, I’d like to add a third way, as an additional safety loop and also to protect both sides.

Members have to be able to give their input with confidence that their voice will be heard. Often, this will be little things like small requests around software or services, little pointers like an item on a platform that needs to be flagged as inappropriate. That means, members have to be able to directly contact the team. Depending on the size of the organization, there can be several things to consider.

- First, we want to protect the staff from too many small requests that require coordination. Some items might be “big” items, some might be small. Some items might be more appropriate to deal with on the board level, some can be dealt with directly by the staff/stewards.

- Second, we cannot expect community members to know who is the best person to talk to. Therefore, we have to filter the in-going information, which is why I am using the imagery of a mailbox. There can be specific requests (formal resolutions) or little tweaks.

In a sociocratic organization with a clean separation between management (operations coordination) and board, the best place to accept input is the operations coordinators. They can send requests and input `up’ to the board or `down’ into a work circle. In a small organization, this might happen by responding to the catch-all email, or a more sophisticated work flow with extra staff in a large organization.

The reason I am adding this extra measure is because a forum or any comparable means of gathering does not satisfy all the needs. There might be people who live further away or are homebound and cannot attend a gathering. There might be members who cannot spend as much time in a forum discussing details of policy. There might be language barriers, technical barriers, other time constraints. Therefore, the mailbox is the safety measure so every member can speak up if they need to. (Some organizations run a system of `decisions by those who write the most emails’ which equates to people monopolizing air time during in-person meetings. We don’t want to give attention only relative to how much it is being discussed.)

The `mailbox’ can take very different shapes and has to be designed appropriate to the given context. Also, the mailbox can potentially work faster than any other form of communication. If we attached the mailbox to the board, response time would probably go down because average boards do not meet as often. The operations coordination is constituted by the people who are deep into the actual operations anyway which guarantees the most immediate response.

This complements representation on the board: if the community delegates do not hear a member’s concern, then one can submit that concern through the mailbox. If — for whatever reason — the mailbox fails, then the community member can get the delegates’ attention. Or we join the discussion and exploration in the forum to be heard. Three different channels of giving feedback while neither overloading the board or the staff are a very safe and doable way of connecting members and staff/stewards.

Closing

I hear a lot of vagueness in “we want democratic governance” of a cooperative. To me, neither the approach of “we all run this together” nor the idea of “let’s just let members vote once every other year” is satisfying. If we lack intentionality and clarity around the how of democratic governance, we risk compromising either member voice or effectiveness of the operations. In this article, I aimed to give the operational business as much autonomy to act as possible while strengthening member voice for input in a way that can be heard well by the decision-makers. Several feedback loops through different channels make it easier to build a transparent, trustful relationship.

I outlined an architecture that can be tailored to the specific context of the platform cooperative and that dovetails well with any form of governance. The intention is to give people more choice in how they design the governance of their platform and to make egalitarian governance, built on trust, more doable and successful.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.